Mike R. Curran

Redecorating

Bade Turgut

07/2020Over the past two years, Bade Turgut︎︎︎ has documented her grandmother's home in Tarsus, Turkey. Redecorating brings those photographs to life in a Minneapolis apartment rearranged to resemble that home. Viewed alongside an installation piece that examines Turkish history, the show becomes a space where family lore and national narratives are both honored and contested.

Installation images by Bade Turgut.

Curatorial Essay

We wander through the cavernous underbelly of St. Paul’s largest antique mall, searching for objects that remind Bade of her grandmother’s home in Tarsus, Turkey. “How about this one?” I ask, holding up a throw pillow depicting a pastoral scene. “No, that doesn’t feel right,” Bade replies, before bringing her attention back to a basket filled with table runners.

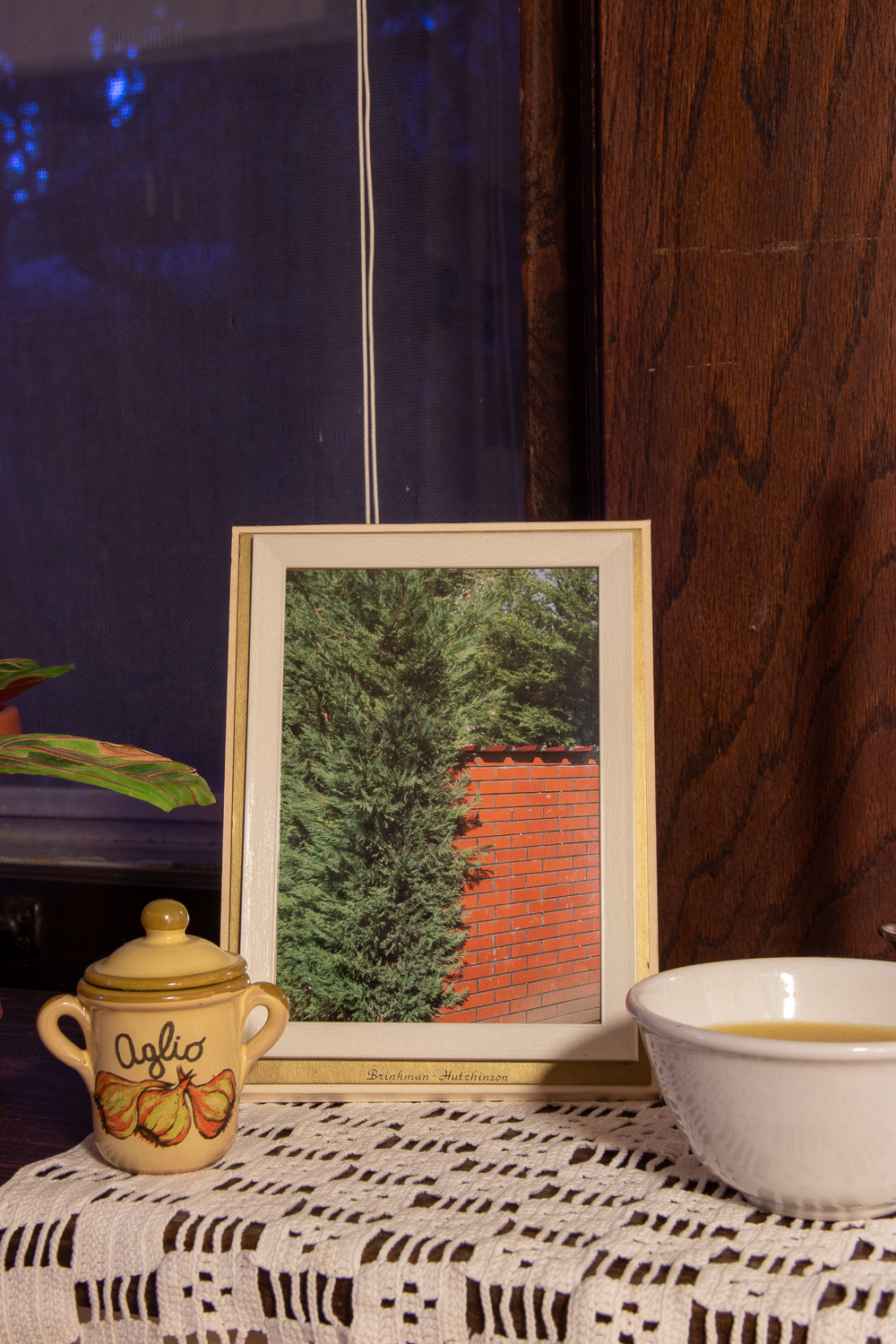

Her rejection of the throw pillow is well-founded. The Midwestern gaudiness of the items we pass seem clumsy compared to the delicate details of Birsen’s home, where the doilies are hand-crocheted and plastic fruits are carefully wrapped in cellophane. In this home, a landline phone sits atop a heart-shaped quilted pillow, its twisted cord suggesting that Birsen just ended a long-distance phone call. In the next room, a collection of ten family photographs fan across a tabletop in heavy metallic frames of varying sizes, the age of their subjects spanning generations. These are the tender scenes that Bade has preserved in her photos.

In Tarsus, a wallet-sized portrait of a nephew is taped onto the corner of a maritime painting, and a silver frame holding a black and white image of nine family members rests on a couch cushion. With Redecorating, Bade has worked her photographs into the furniture in similar ways. She is concerned less with creating fine art prints than with reconstructing a domestic landscape where a photograph is a permanent fixture—as much part of the home as the dining table or kitchen sink.

Perhaps selfishly, I am drawn to Bade’s photographs because of how they remind me of the home that my own grandmother makes, where angel statuettes occupy every available surface and the plush white carpet stays cool under late summer heat. But, like the cluttered side table that Birsen hides from guests, my grandmother’s home also hosts a list of unknowns: stairs to a basement that I will never descend, and rumors of cash stashed in the freezer.

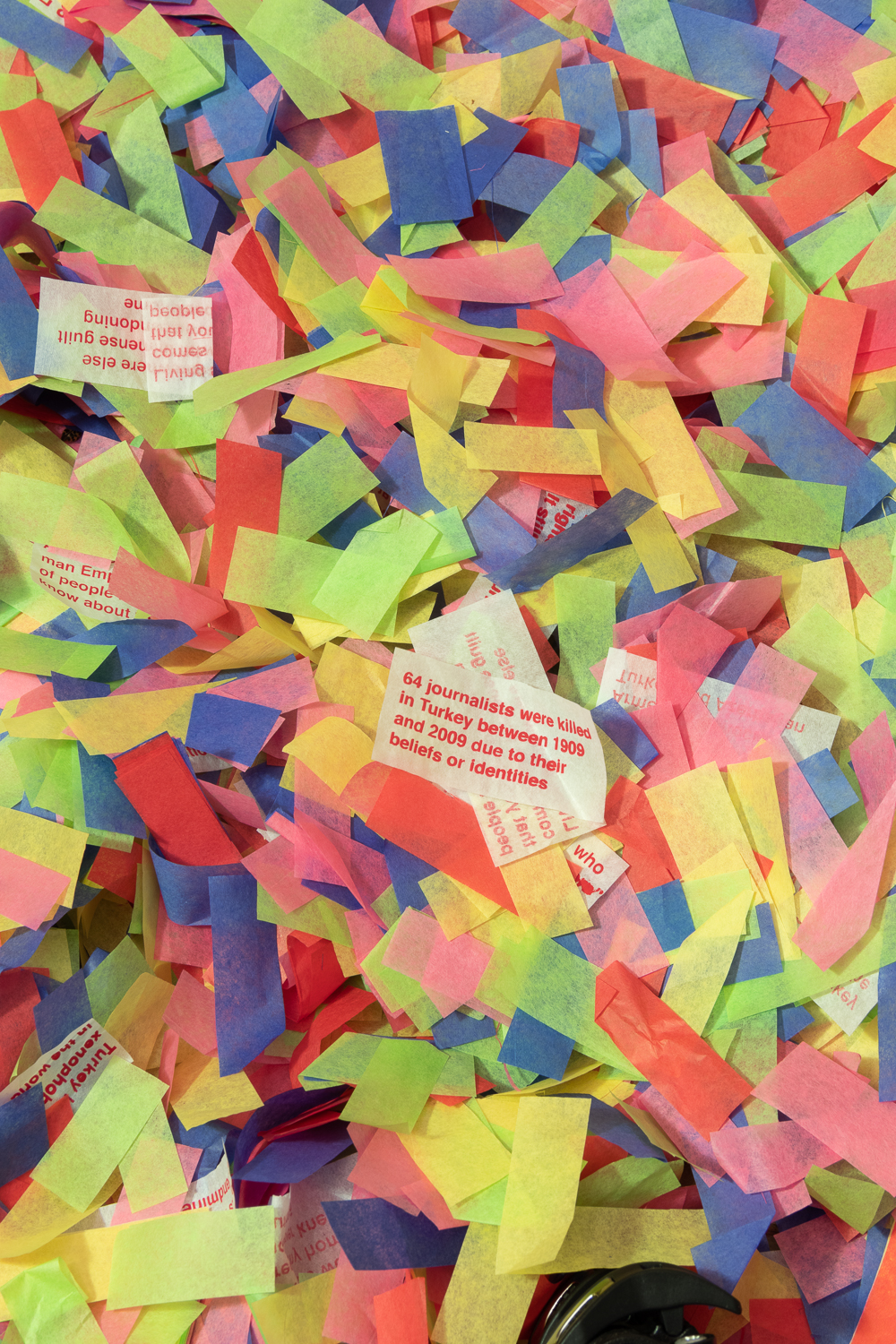

At the outset, Bade and I joked that this show would celebrate the “universal grandma”—an ode to figurines, wall calendars, and flowers that you have to smell to confirm they are fake. But Redecorating does not claim any truisms. Instead, it emerges from Bade’s distinct desire to document Birsen’s life through the objects she has amassed. Viewed alongside Party’s Over—an installation of confetti paper and deflated balloons that confronts Turkey’s onerous history of state-sanctioned violence—the show becomes an attempt at reconciling family lore and nationalized narratives, oscillating between secrecy and pride. It is a show interested in presence as much as it is in absence. On a more intimate scale, Redecorating could be read as a devotional gesture made to Birsen from 6,000 miles away.

With that distance, though, comes necessary distortion. We have not perfectly reproduced Birsen’s home. The fruit at Normal Residential Purposes feels a little more plasticky; items sourced from an antique mall in a state with its own fraught collective memory feel more tacky than authentic. But maybe that shoddiness is the point. Family memories, just like national histories, are inherently fragmented, constantly collapsing and rebuilding and collapsing again. What Bade has invented out of that tension is a space where family memory is both preserved and expanded upon. It is a gesture borne out of love.

Her rejection of the throw pillow is well-founded. The Midwestern gaudiness of the items we pass seem clumsy compared to the delicate details of Birsen’s home, where the doilies are hand-crocheted and plastic fruits are carefully wrapped in cellophane. In this home, a landline phone sits atop a heart-shaped quilted pillow, its twisted cord suggesting that Birsen just ended a long-distance phone call. In the next room, a collection of ten family photographs fan across a tabletop in heavy metallic frames of varying sizes, the age of their subjects spanning generations. These are the tender scenes that Bade has preserved in her photos.

In Tarsus, a wallet-sized portrait of a nephew is taped onto the corner of a maritime painting, and a silver frame holding a black and white image of nine family members rests on a couch cushion. With Redecorating, Bade has worked her photographs into the furniture in similar ways. She is concerned less with creating fine art prints than with reconstructing a domestic landscape where a photograph is a permanent fixture—as much part of the home as the dining table or kitchen sink.

Perhaps selfishly, I am drawn to Bade’s photographs because of how they remind me of the home that my own grandmother makes, where angel statuettes occupy every available surface and the plush white carpet stays cool under late summer heat. But, like the cluttered side table that Birsen hides from guests, my grandmother’s home also hosts a list of unknowns: stairs to a basement that I will never descend, and rumors of cash stashed in the freezer.

At the outset, Bade and I joked that this show would celebrate the “universal grandma”—an ode to figurines, wall calendars, and flowers that you have to smell to confirm they are fake. But Redecorating does not claim any truisms. Instead, it emerges from Bade’s distinct desire to document Birsen’s life through the objects she has amassed. Viewed alongside Party’s Over—an installation of confetti paper and deflated balloons that confronts Turkey’s onerous history of state-sanctioned violence—the show becomes an attempt at reconciling family lore and nationalized narratives, oscillating between secrecy and pride. It is a show interested in presence as much as it is in absence. On a more intimate scale, Redecorating could be read as a devotional gesture made to Birsen from 6,000 miles away.

With that distance, though, comes necessary distortion. We have not perfectly reproduced Birsen’s home. The fruit at Normal Residential Purposes feels a little more plasticky; items sourced from an antique mall in a state with its own fraught collective memory feel more tacky than authentic. But maybe that shoddiness is the point. Family memories, just like national histories, are inherently fragmented, constantly collapsing and rebuilding and collapsing again. What Bade has invented out of that tension is a space where family memory is both preserved and expanded upon. It is a gesture borne out of love.