︎︎︎

From 2018 – 2020, Bade Turgut︎︎︎ documented her grandmother's home in Tarsus, Turkey. Redecorating brought those photographs to life in a Minneapolis apartment rearranged to resemble that home. Viewed alongside an installation piece that examines Turkish history, the show became a space where family lore and national narratives could be both honored and contested.

Artist Statement

by Bade TurgutMy grandmother was the family photographer for all of the post-retirement trips she took with my grandfather. Her house is full of physical albums and photos of him in almost every corner of the house. A significant memory from my childhood is of her repetitively asking if I remembered my grandfather, who passed away when I was six years old. I frankly don’t know if I would have if it wasn’t for the pictures.

During the winter of 2018, visiting Turkey after a year away, I found myself frantically photographing my grandmother’s house. Her house is a floor below where I grew up; I spent most of my time there after school before my parents got home. Now, living abroad for five years, I always wonder how things will change during the time I’m not there. In a way, photographing my grandmother’s house was a way to deal with her loss before I lost her. I kept wondering how the house would look different when she was not around anymore.

After scrutinizing every corner to see what I could photograph, I started thinking about objects as markers of time and memory of her life of 79 years. Her sewing machine, bridal gown, and photographs of family members all had stories attached to them. Simultaneously, these objects made me think about the things I did not know about her—or things I never dared ask.

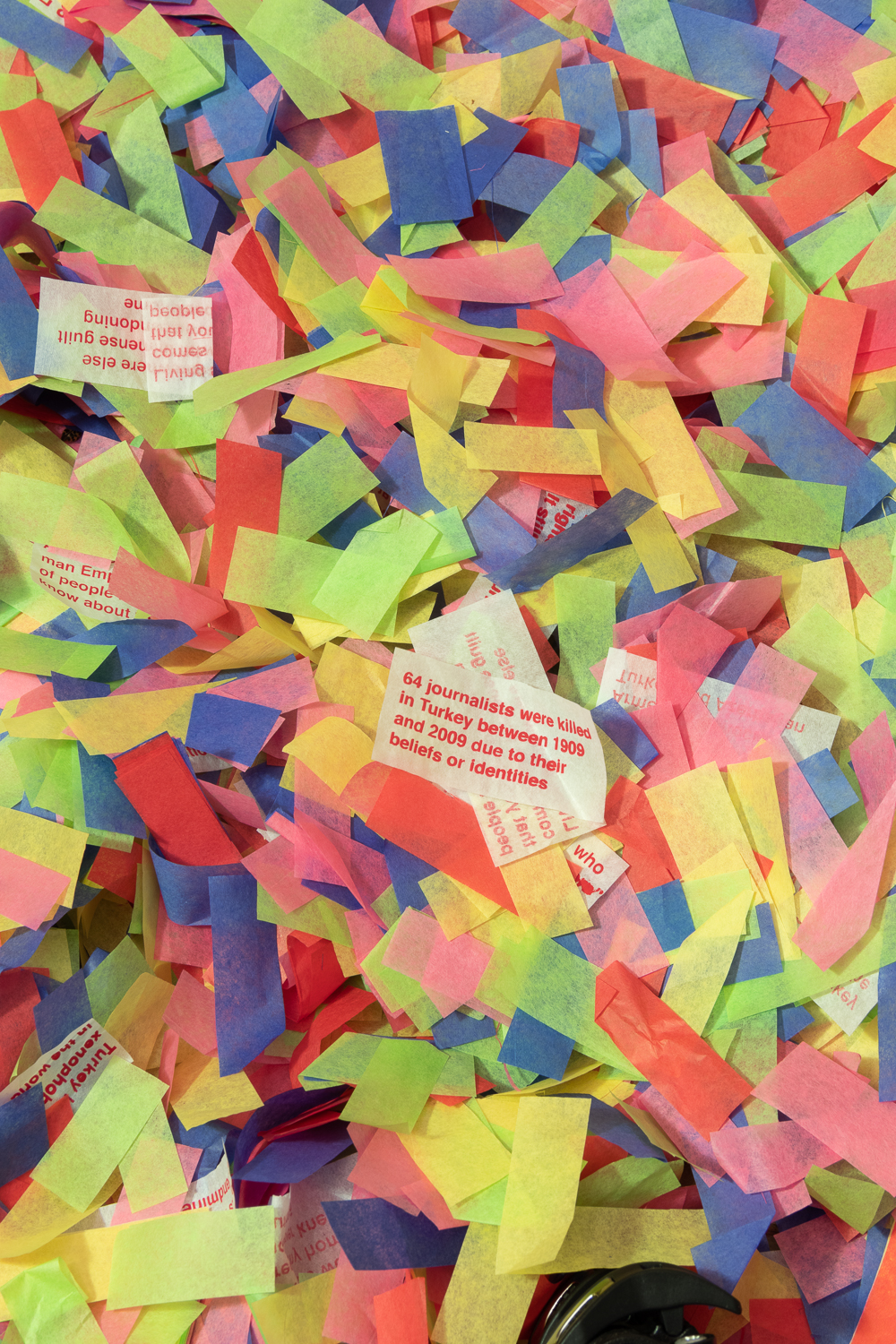

In 2019, I created Party’s Over, an installation piece that is made up of confetti and screen printed statements about Turkey’s political and historical truths, most of which I did not grow up learning. The project was made out of my own political frustrations around the unspoken but undeniable markers of Turkish history. Each of these confrontational statements explore Turkey’s state-controlled, collective—and selective—memory, systematic attacks on truth production, and my personal experiences with these issues.

Though these two works were created with different ideas, tones, and materials, there is something really similar between the missing bits from my grandmother’s life and the national truths that were intentionally kept away from me as a Turkish woman.

Exhibition Essay

by Mike CurranWe wander through the cavernous underbelly of St. Paul’s largest antique mall, searching for objects that remind Bade of her grandmother’s home in Tarsus, Turkey. “How about this one?” I ask, holding up a throw pillow depicting a pastoral scene. “No, that doesn’t feel right,” Bade replies, before bringing her attention back to a basket filled with table runners.

Her rejection of the throw pillow is well-founded. The Midwestern gaudiness of the items we pass seem clumsy compared to the delicate details of Birsen’s home, where the doilies are hand-crocheted and plastic fruits are carefully wrapped in cellophane. In this home, a landline phone sits atop a heart-shaped quilted pillow, its twisted cord suggesting that Birsen just ended a long-distance phone call. In the next room, a collection of ten family photographs fan across a tabletop in heavy metallic frames of varying sizes, the age of their subjects spanning generations. These are the tender scenes that Bade has preserved in her photos.

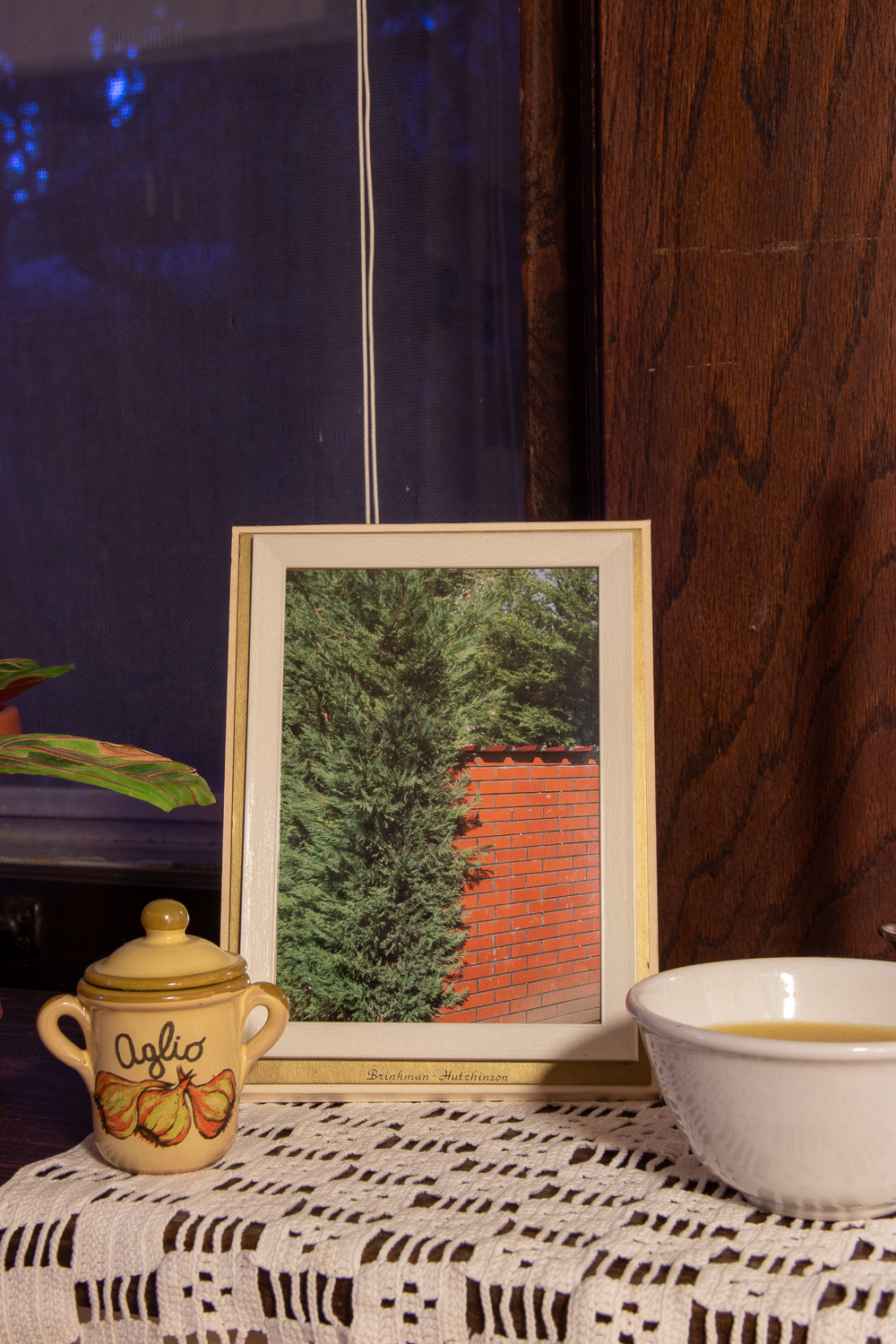

In Tarsus, a wallet-sized portrait of a nephew is taped onto the corner of a maritime painting, and a silver frame holding a black and white image of nine family members rests on a couch cushion. With Redecorating, Bade has worked her photographs into the furniture in similar ways. She is concerned less with creating fine art prints than with reconstructing a domestic landscape where a photograph is a permanent fixture—as much part of the home as the dining table or kitchen sink.

Perhaps selfishly, I am drawn to Bade’s photographs because of how they remind me of the home that my own grandmother makes, where angel statuettes occupy every available surface and the plush white carpet stays cool under late summer heat. But, like the cluttered side table that Birsen hides from guests, my grandmother’s home also hosts a list of unknowns: stairs to a basement that I will never descend, and rumors of cash stashed in the freezer.

At the outset, Bade and I joked that this show would celebrate the “universal grandma”—an ode to figurines, wall calendars, and flowers that you have to smell to confirm they are fake. But Redecorating does not claim any truisms. Instead, it emerges from Bade’s distinct desire to document Birsen’s life through the objects she has amassed. Viewed alongside Party’s Over—an installation of confetti paper and deflated balloons that confronts Turkey’s onerous history of state-sanctioned violence—the show becomes an attempt at reconciling family lore and nationalized narratives, oscillating between secrecy and pride. It is a show interested in presence as much as it is in absence. On a more intimate scale, Redecorating could be read as a devotional gesture made to Birsen from 6,000 miles away.

With that distance, though, comes necessary distortion. We have not perfectly reproduced Birsen’s home. The fruit at Normal Residential Purposes feels a little more plasticky; items sourced from an antique mall in a state with its own fraught collective memory feel more tacky than authentic. But maybe that shoddiness is the point. Family memories, just like national histories, are inherently fragmented, constantly collapsing and rebuilding and collapsing again. What Bade has invented out of that tension is a space where family memory is both preserved and expanded upon. It is a gesture borne out of love.

Photographs by Bade Turgut.